Digital health can be a lifeline for people in maternity care deserts

A shocking number of pregnant people in the U.S. live in communities with no maternity care options. In fact, 35 percent of counties nationwide are maternity care deserts — they lack obstetric care providers as well as hospitals and birth centers offering obstetric care.1

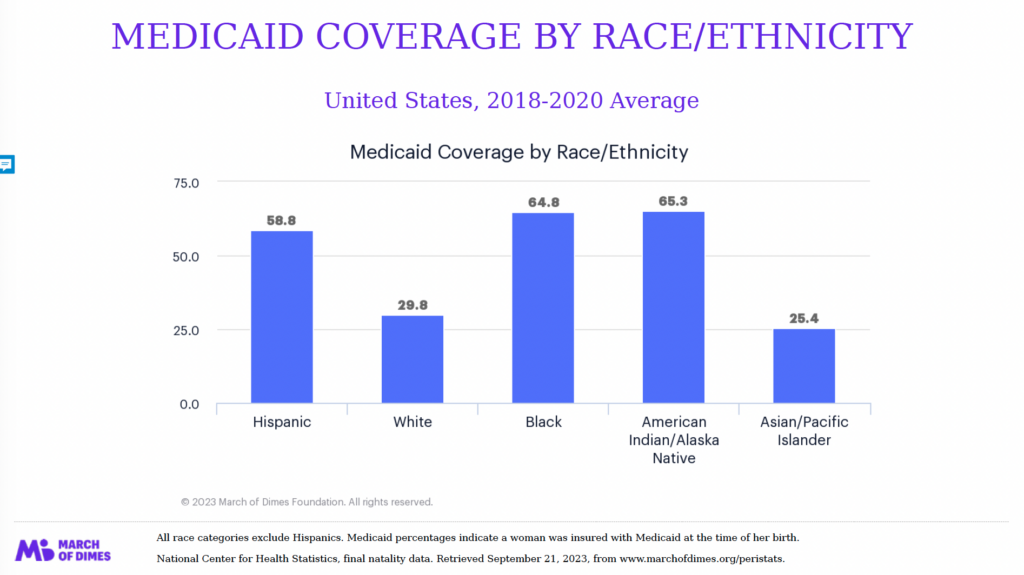

Being pregnant in a community without care is already a health risk, but when we look at a map of maternity care deserts, we see that the risks run even deeper. Maternity care deserts are concentrated in the Midwest and South. Overlay this map with a map of private health insurance coverage, and a pattern emerges: A high percentage of mothers in maternity care deserts, especially in Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida, are Medicaid beneficiaries.

Women who are most likely to be pregnant in a maternity care desert are 28.85 percent more likely than women in other parts of the country to be Medicaid beneficiaries. Here’s the breakdown of births covered by Medicaid in 2020 in each of these states:

- Texas: 50.7 percent.2

- Mississippi: 61 percent.3

- Alabama: 50.2 percent.4

- Georgia: 47.2 percent.5

- Florida: 46.8 percent.6

As we can see, in addition to a lack of local care, pregnant women in maternity care deserts are more likely to lack financial resources, which impacts health and nutrition and the ability to travel for care.

Maternity care deserts also tend to be communities with a higher percentage of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) mothers, who face higher health risks during pregnancy than their white counterparts. Consider this: Black women are three times more likely than white women to die from a pregnancy-related health complication.7

For payers, who spend an estimated $75.8 billion each year on maternal and postpartum health,8 and for Medicaid plans, which cover 42 percent of births in the U.S. each year,9 lowering risks and improving birth equity for women in maternity care deserts is an urgent matter. To address this challenge, payers need to understand some of the unique barriers to care in underserved communities.

Stigma and history impact how people approach medical care

Cultural and historical factors can make it harder to reach and serve the Medicaid population. Stigma around social services can keep people from accessing the care that’s available.10 And many worry because public programs can be affiliated with child protective services (CPS). One study of low-income mothers in Rhode Island, for example, found that one in six respondents had declined services because of concerns about CPS reports.11

Additionally, many BIPOC people, who are heavily represented in maternity care deserts, have a history of mistreatment by the medical establishment. They more likely to have experienced medical gaslighting,12 or to have visited doctors who dismissed their symptoms and ignored their pain.13 They may be wary of the medical system because of the history of abuse — events such as the Tuskegee Experiment and forced sterilization programs in the early and mid 1900s are still fresh in people’s minds.

To overcome these barriers, payers need to connect with members through programs that are trusted, culturally sensitive, community-focused, and tailored to each individual person’s needs and concerns.

How a digital health solution, combined with community-based health, can serve people in maternity care deserts

Digital health tools are uniquely suited to overcoming geographical barriers and meeting users where they are, in a format they can trust. Digital tools can be designed to take into account how factors, such as race-associated risks and limited resources, impact health. And they can provide an essential link to trusted community resources. For the Medicaid population, digital health can be an essential lifeline. While some initially had concerns digital health wouldn’t be accessible to this population due to smartphone affordability, recent studies have found that Medicaid users use smartphones and tablets at the same rate as the general U.S. population.14

Ovia’s digital health solution is built with all of these ideas in mind. We help pregnant people in maternity care deserts to understand their health and find the best possible care by:

- Tracking their symptoms and sending alerts when a symptom requires medical attention.

- Delivering personalized risk assessments that empower people to advocate for tests and care when needed.

- Offering personalized health pathways to help manage health

- Providing the tools to choose the closest and safest place to give birth.

- Connecting them with community-based advocates and providers, like doulas and midwives

- Helping dispel myths about government assistance programs like WIC and connect women with the support they qualify for and nutritious foods

- Improving health literacy and advocacy with proven behavioral frameworks

Ovia is also built on a deep understanding that not all experiences of pregnancy are the same, and every person deserves care that’s tailored to their own needs. We provide a pathway and module built specifically for Black women. Our members are invited to request coaching from specialists with similar racial and cultural backgrounds to their own, an approach that can help improve health outcomes.15

Another component digital health can help with is building connection to trusted community support. We help users access the resources they need for their health and wellbeing, such as WIC, which is shown to improve physical and mental health outcomes for mothers and their children. And Ovia helps pregnant people find community care advocates and community-based providers, including doulas and midwives.

To support pregnant people in maternity care deserts, payers need to think beyond traditional engagement models. A thoughtful digital solution, tied closely to trusted, community-based resources, can help improve health outcomes and birth equity while lowering costs — and it can make a huge difference for pregnant people who urgently need safer, better care.

Want to learn more? Ovia is here for you.

Ovia Health, a Labcorp subsidiary, has served more than 18 million family and parenthood journeys since 2012 and is on a mission to make a happy, healthy family possible for everyone. Ovia Health is the only family health solution clinically proven to effectively identify and intervene with high-risk conditions. The company’s 50+ clinical programs, including predictive coaching and personalized care plans, help prevent unnecessary health care costs, improve health outcomes, and foster a family-friendly workplace that increases retention and return to work. For more information, visit OviaHealth.com.

1: March of Dimes: https://www.marchofdimes.org/maternity-care-deserts-report

2: March of Dimes: https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?reg=99&top=11&stop=154&lev=1&slev=4&obj=1&sreg=48&creg

3: Center for Mississippi Health Policy: https://mshealthpolicy.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Post-Partum-Medicaid-Feb-2021.pdf

4: March of Dimes: https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?reg=99&top=11&stop=154&lev=1&slev=4&obj=1&sreg=01

5: March of Dimes: https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?reg=13&top=11&stop=154&lev=1&slev=4&obj=1&sreg=13

6: March of Dimes: https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?reg=12&top=11&stop=154&lev=1&slev=4&obj=1&sreg=12

7: Centers for Disease Control: https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/features/maternal-mortality/index.html

8: Maternal and Child Health Journal: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21318294/

9: Medicaid.gov: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/quality-improvement-initiatives/maternal-infant-health-care-quality/index.html

10: SSM – Population Health: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9127679/

11: Casey Family Programs: https://www.casey.org/media/20.07-QFF-RFF-Concealment-and-constraint-in-institutional-engagement.pdf

12: Canadian Medical Journal Association: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9828884/

13: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4843483/

14: Deloitte: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/mobile-health-care-app-features-for-patients.html

15: Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33403653/.